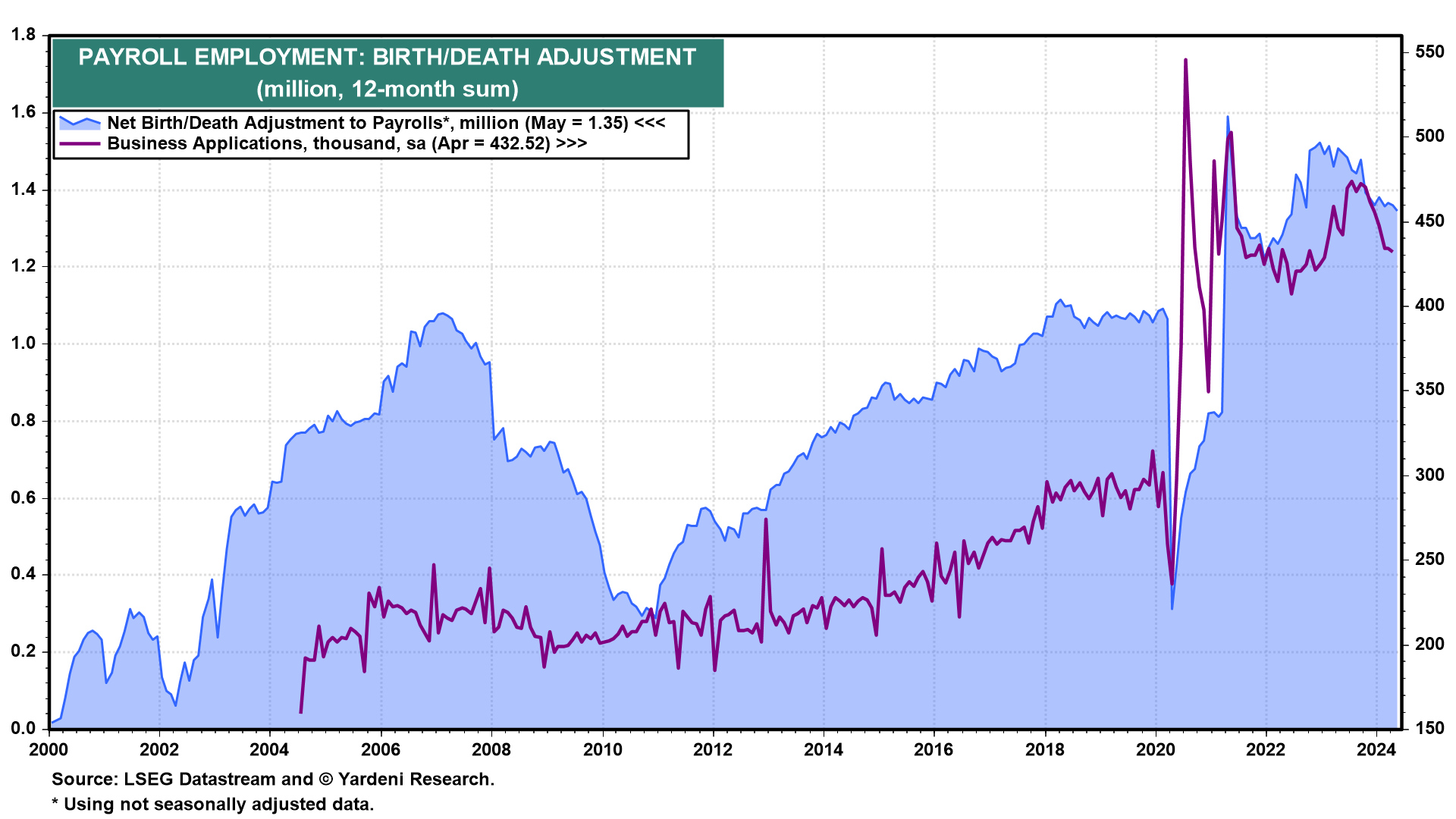

Some economists claim that recent nonfarm payroll gains are misleadingly strong and are masking the underlying weakness in the labor market. These die-hard hard-landers point to a wonky calculation by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), i.e., the Birth/Death Adjustment (B/D).

The B/D Adjustment attempts to account for job gains attributable to new businesses and job losses due to business closures that don't show up in the BLS survey of employers about the number of their payroll workers. Some say the BLS is underestimating the number of business failures due to the pandemic and the sharp increase in interest rates since early 2022. So the payroll employment series is too high, as confirmed by the much weaker household employment survey.

Here's why we (and the markets) are not as concerned as the hard-landers:

(1) Payrolls. The B/D Adjustment added roughly 1.35 million payroll jobs in the past 12 months, accounting for a significant portion of the 2.76 increase in payroll employment over the same period (chart). In the 12 months through February 2020, just before the pandemic, BLS added about 1.1 million jobs.

(The monthly B/D series is not seasonally adjusted (nsa) before it is added to the nsa survey-based series. The sum of the two is then seasonally adjusted. Our 12-month approach solves the seasonality issue.)

(2) Business Formation. Separate data collected by the Census Bureau on business formations tracks applications for Employer IDs. The Richmond Fed concluded last August that rising business formation reflected growing entrepreneurship after the pandemic, corroborating the higher B/D Adjustment!

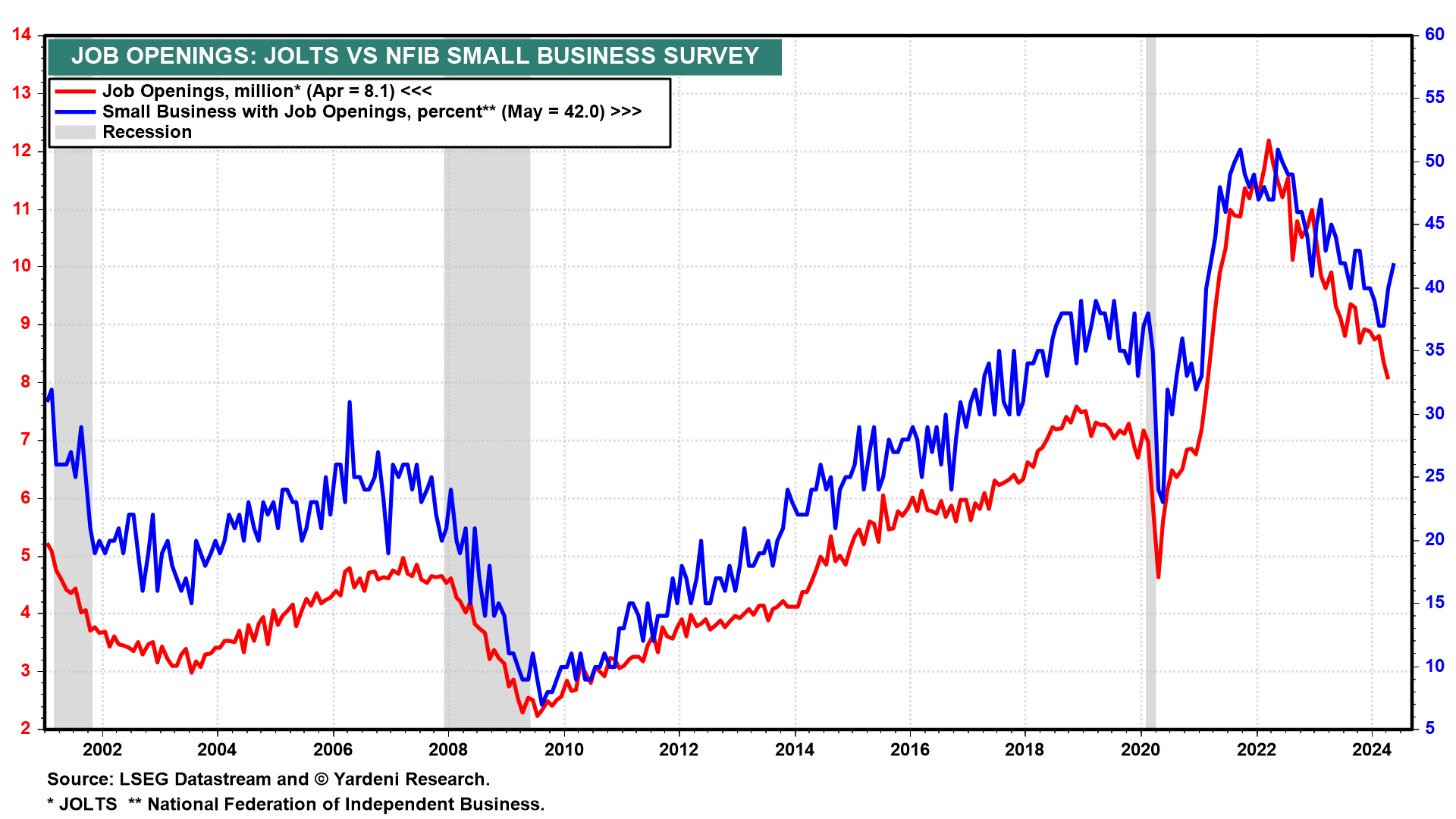

(3) JOLTS. If the B/D Adjustment was masking a weak labor market, would the rest of the jobs picture look so strong? Initial unemployment claims remain very low. Job openings, from the JOLTS and the NFIB surveys, both show a slowing-but-growing labor market, not one that's been getting weaker (chart). In our opinion, the labor market is normalizing from the pandemic.