It’s difficult to count the number of mainstream macro theories that we’ve debunked over the past few years. Many long-used relationships and correlations have been upended by record monetary and fiscal stimulus during the pandemic, a wave of early retirements by Baby Boomers, and interest-rate hikes off ultralow levels. We’ve been busy shooting them down since early 2022.

Taking great pains to keep it short, below is a review of the 10 widely held macro theories that haven’t held water and the reasons that they’ve led many astray:

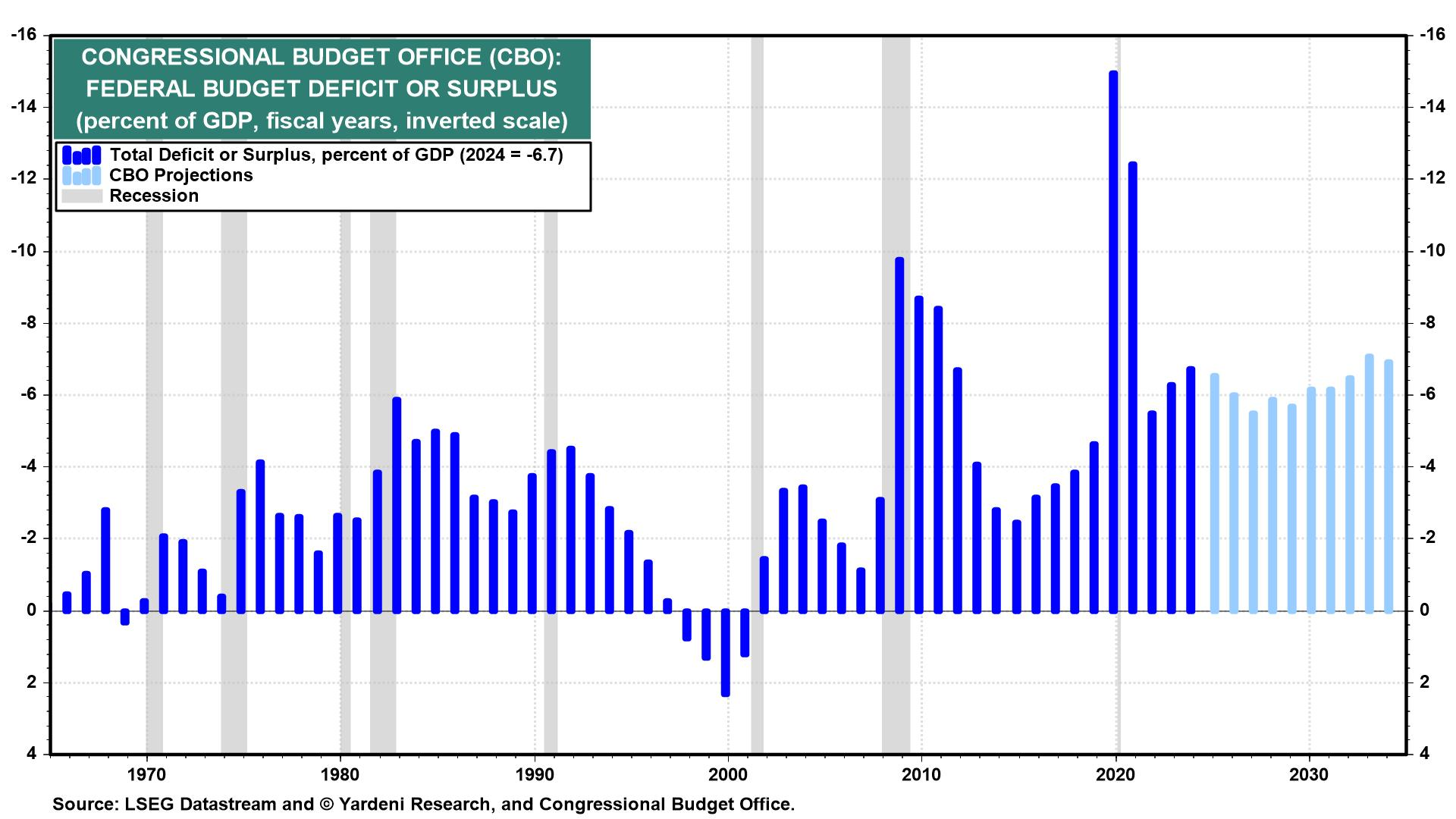

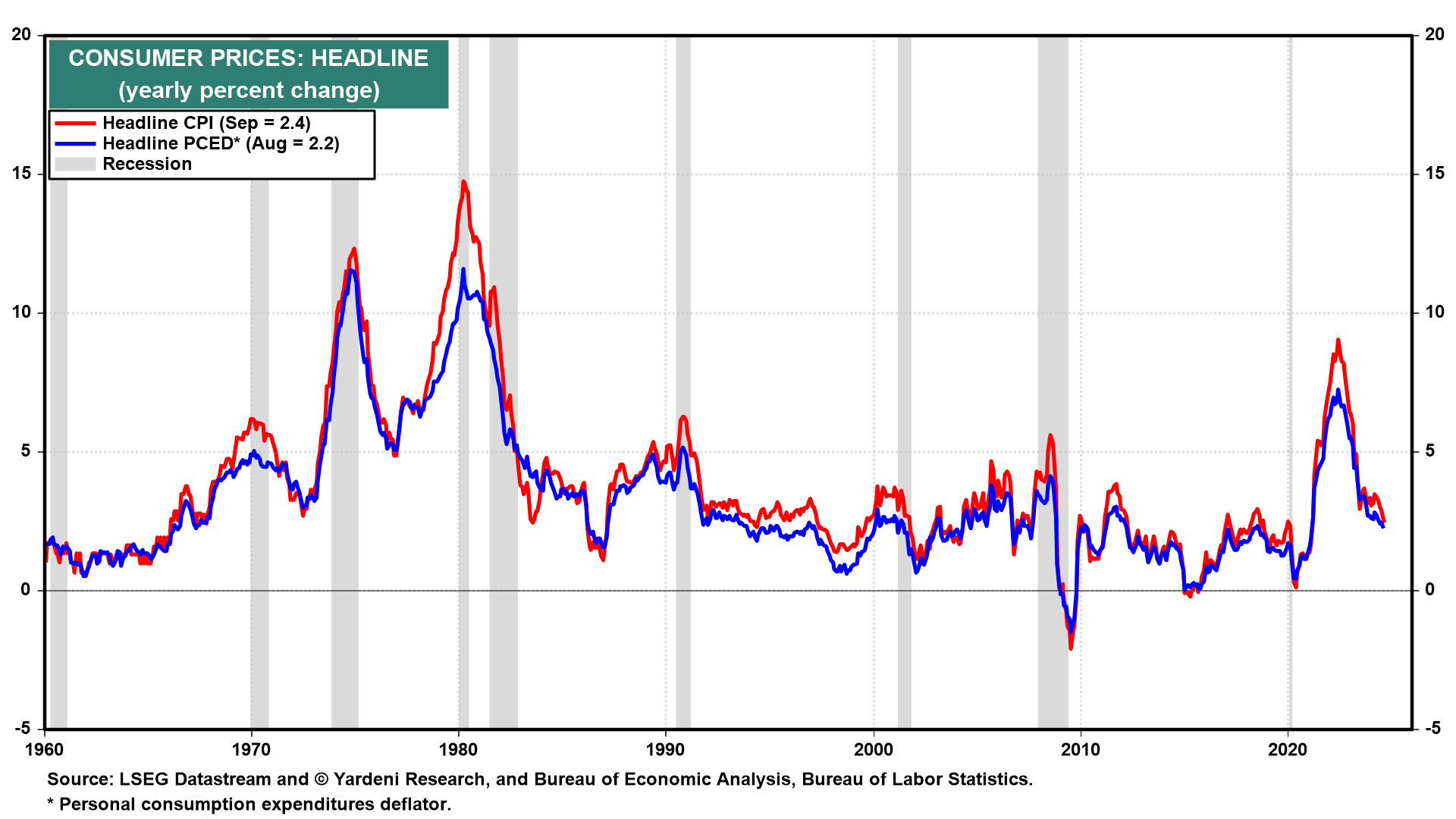

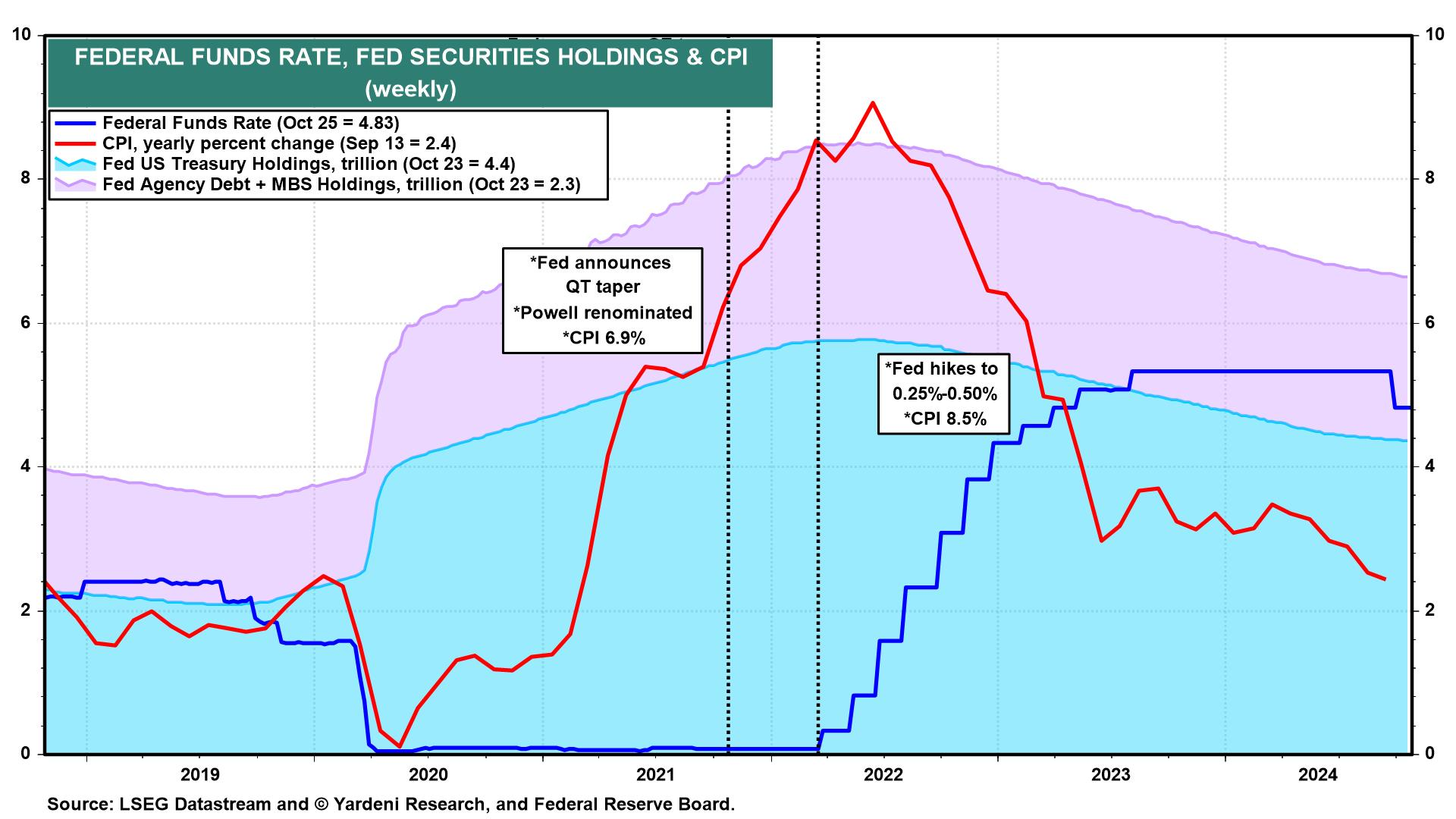

(1) Modern Monetary Theory. Melissa and I have said before that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) isn’t modern, isn’t monetary, and isn’t a theory. MMT’s proposition that a government that borrows in its own currency can finance its spending at will with more debt lost credibility as inflation soared in 2022 and 2023. However, MMT seems to be working now that inflation has subsided. Even as the federal deficit remains very wide—and the consensus is that after the November elections, it will continue to widen—inflation has moderated to near 2.0% (Fig. 14 below and Fig. 15 below).

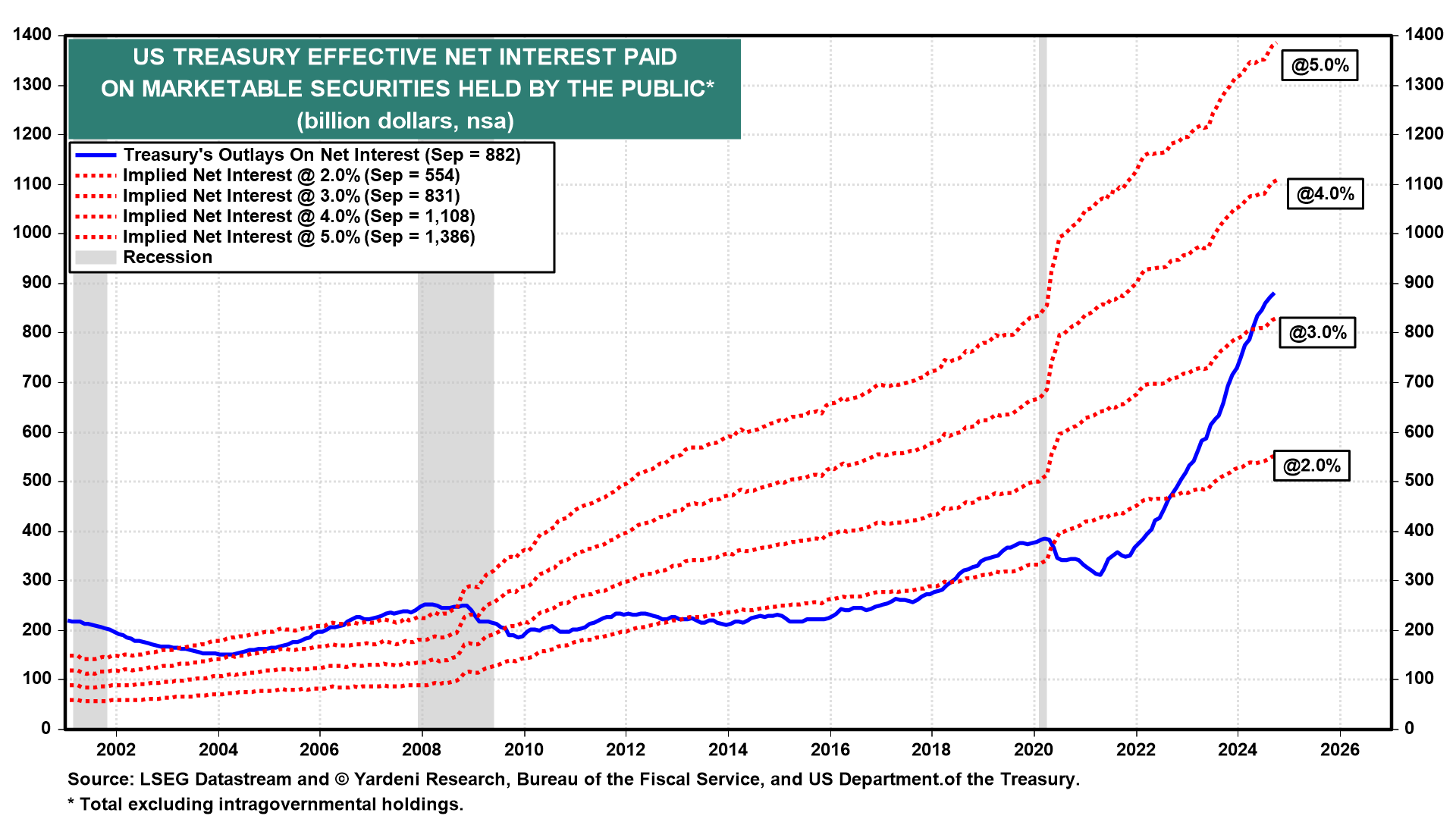

MMT’s zealots within the current administration have been essentially using a blank check to load up on fiscal stimulus even though the economy is already growing faster than 3.0% y/y. The interest cost on the federal debt is increasing rapidly due to the record debt issuance and higher rates (Fig. 16 below).

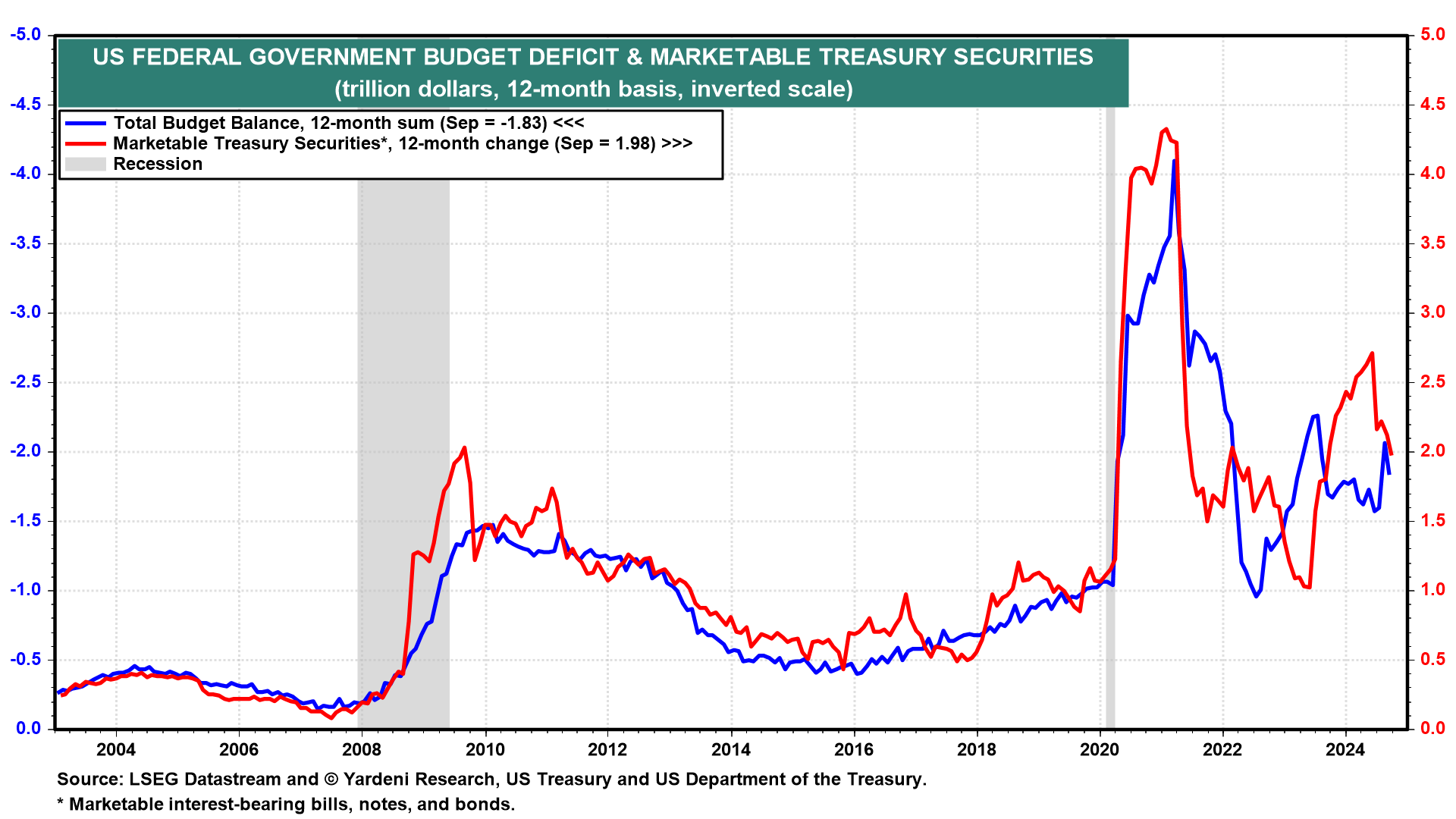

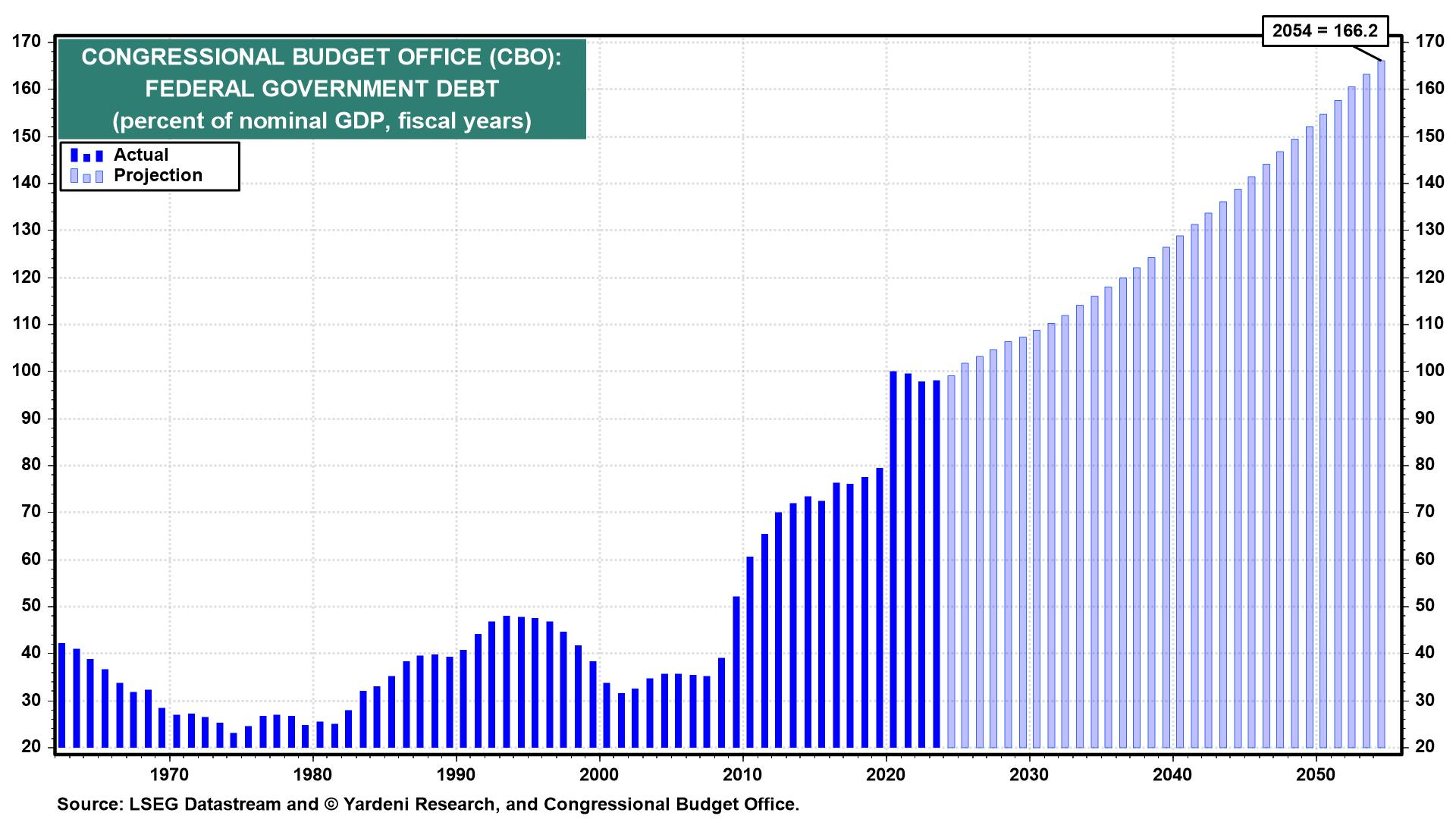

It’s not the Fed’s job to lower rates to accommodate the government, as some have suggested, because that would lead to more inflation. The government instead needs to slow its pace of debt financing (Fig. 17 below). Without doing so, future generations will be saddled with a huge pile of debt that will hamper any stimulus efforts if and when there is a recession (Fig. 18 below).

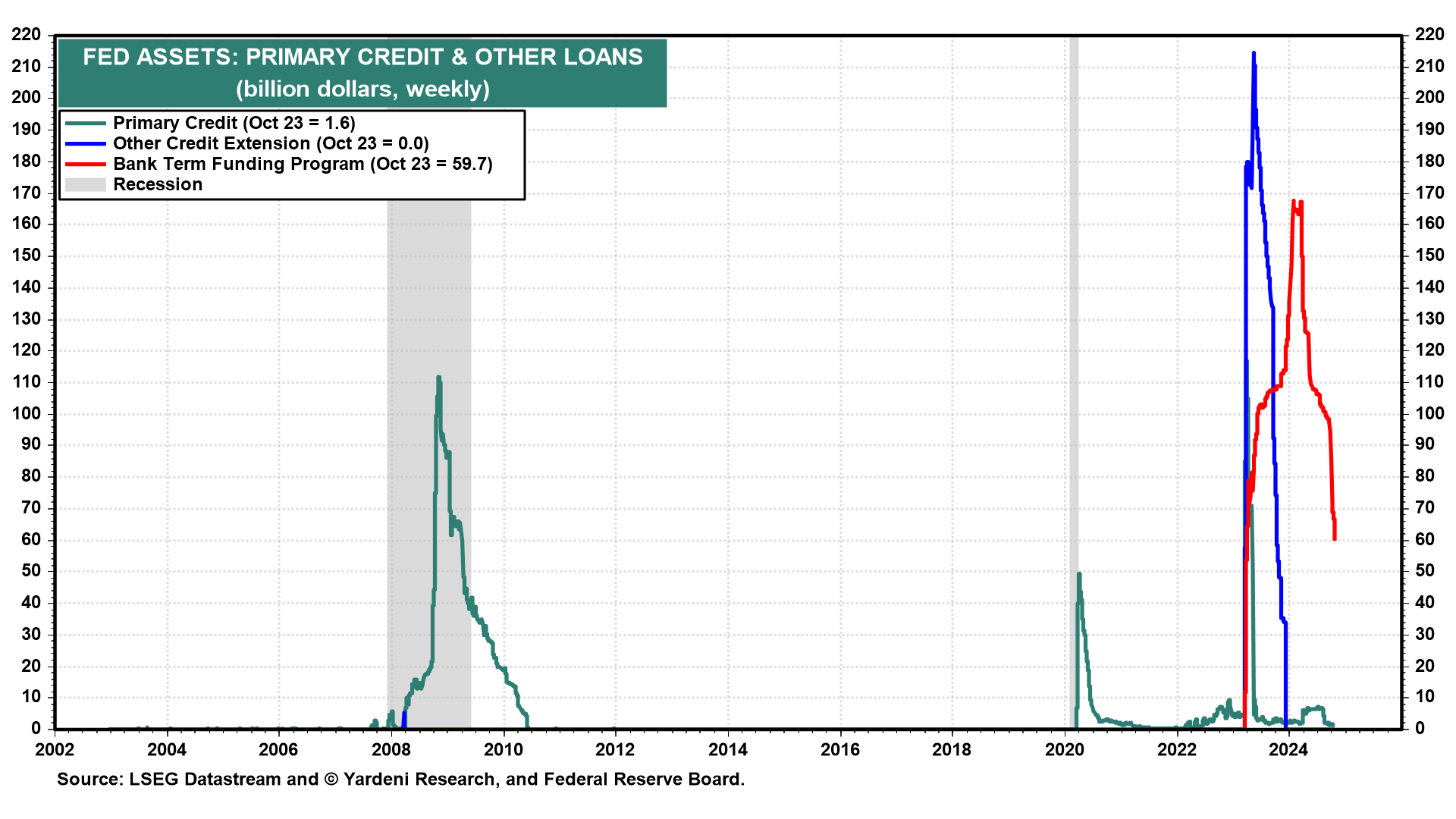

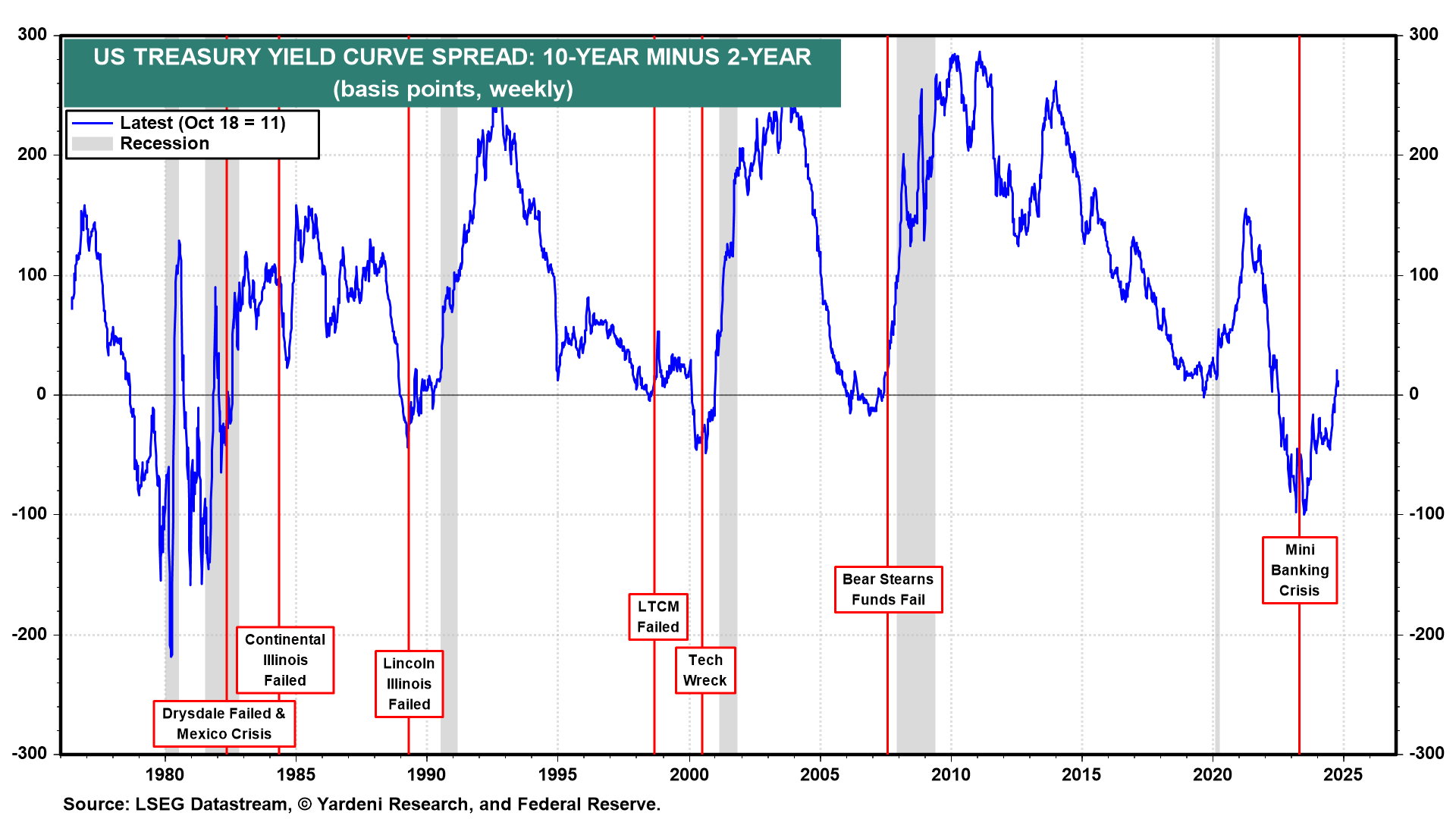

(2) Inverted yield curve. According to our Credit Crisis Cycle theory, the inverted Treasury yield curve signals that bond investors are worried that higher short-term interest rates will cause a credit crisis and therefore a recession. Because the Fed and Treasury prevented a credit crunch from emerging as regional banks collapsed last March, the expansion was able to continue (Fig. 19 below).

(3) Disinverting yield curve. The Treasury yield curve has flipped positive in September, with the 10-year yield now roughly 15bps above the 2-year yield (Fig. 20 below). Historically, a recession has followed soon after such a disinversion—but only because the Fed was cutting interest rates rapidly to stem a crisis, which then morphed into a recession. This time around, the Fed is cutting rates as a preventative measure.

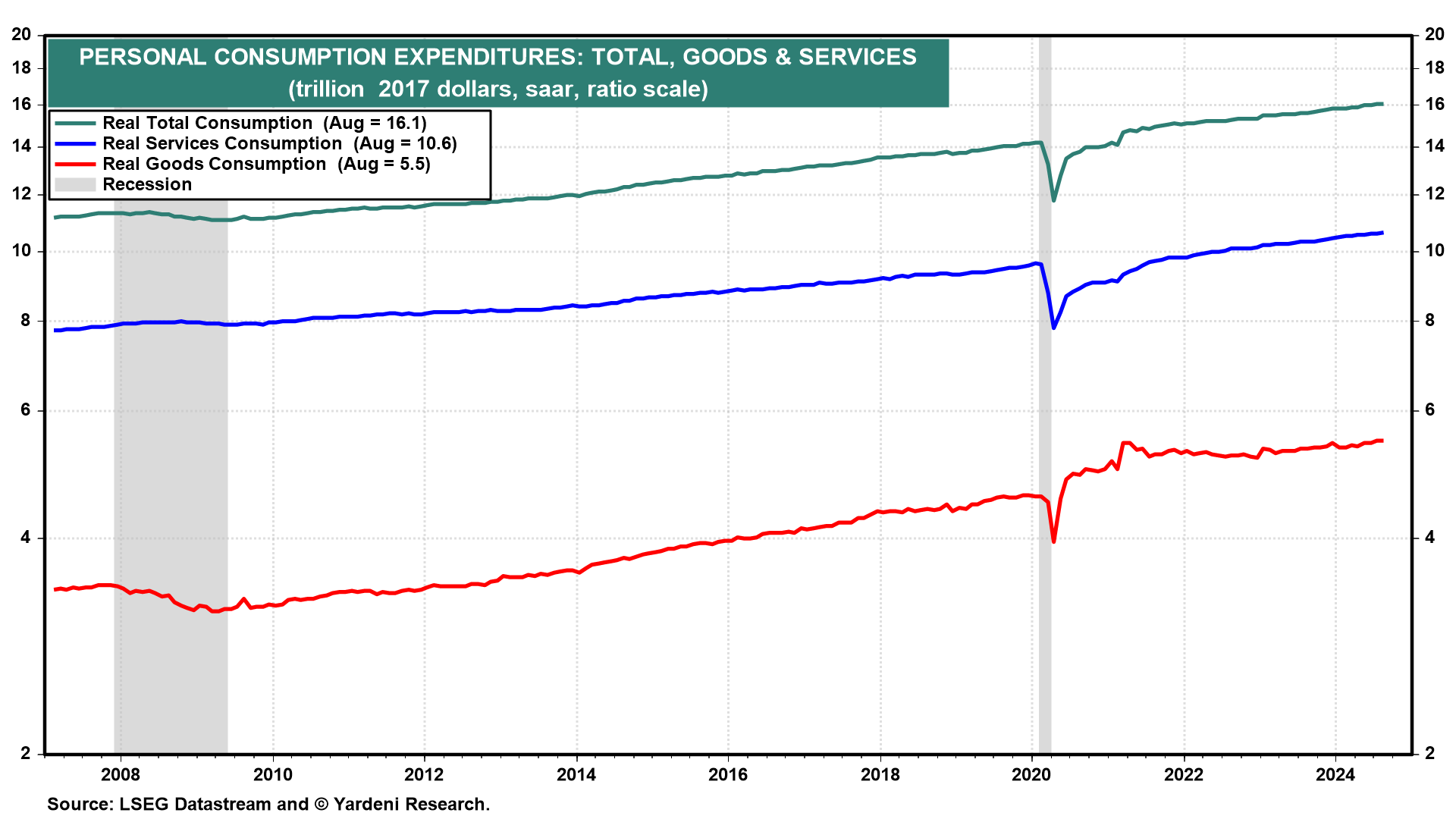

(4) Falling LEI. The 10 components of the LEI are heavily weighted toward the manufacturing sector and include things like the inverted yield curve. That’s led the LEI to inaccurately predict a recession for the past two years. Goods consumption has stagnated at record highs since the Fed raised financing costs and demand for goods decreased after surging during the pandemic (Fig. 21 below). The US economy depends on services versus goods at a roughly 2:1 ratio, rendering the LEI less effective at predicting the economy's performance (Fig. 22).

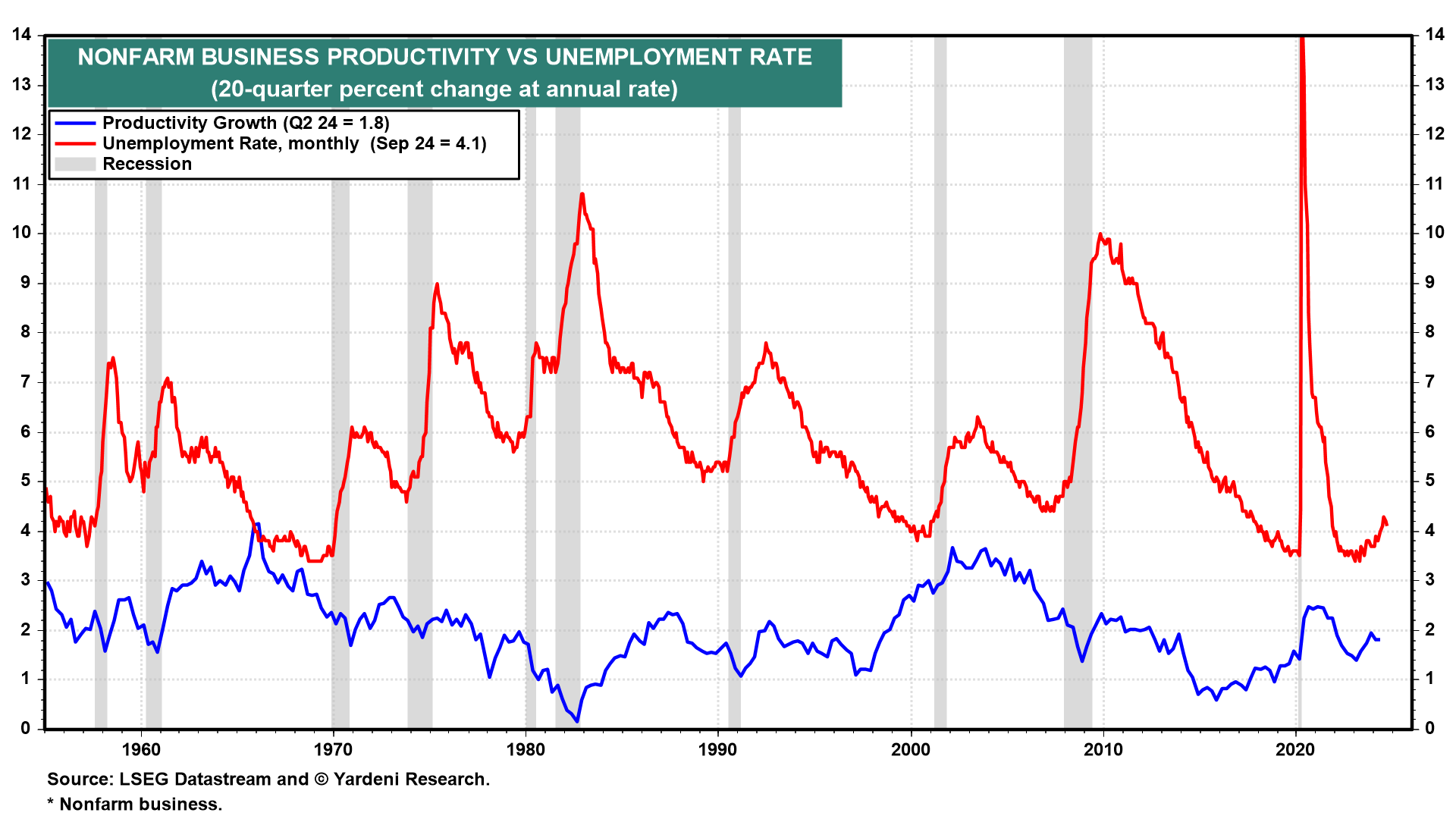

(5) Phillips Curve. The Phillips Curve model is based on the inverse correlation between wage and price inflation versus the unemployment rate (Fig. 23). However, it ignores the inverse relationship between the unemployment rate and productivity growth. So inflation was able to fall in this cycle without a recession, in part because the tight labor market promoted investments that improved productivity (Fig. 24 below).

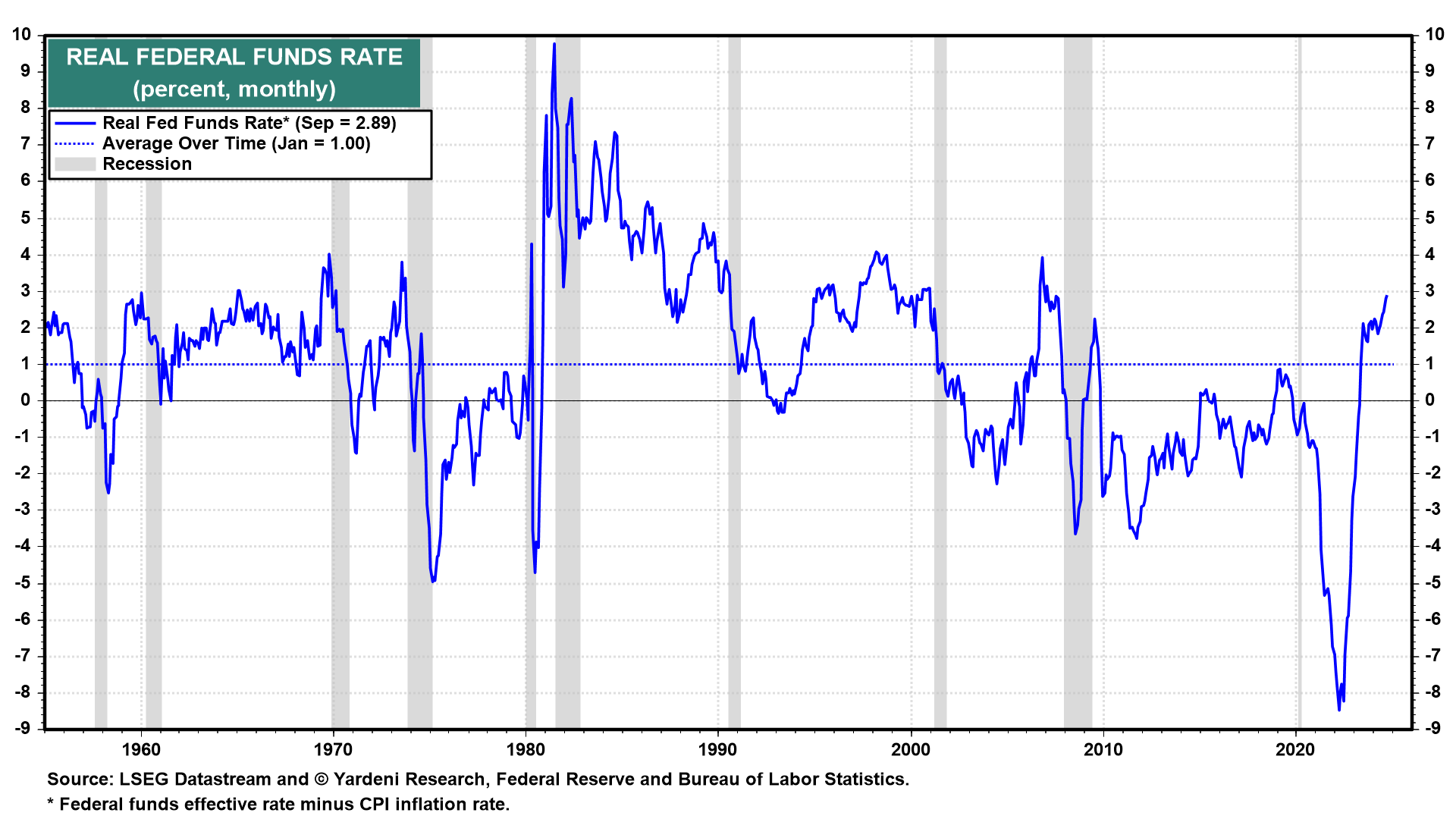

(6) Neutral interest rate. Doves on the FOMC advocate for cutting the federal funds rate (FFR) in order to maintain a neutral real FFR. Their worry is that as inflation falls, the real FFR gets tighter and exerts unnecessary pressure on the economy (Fig. 25 below). We think that adjusting an overnight borrowing rate (which few consumers or businesses actually use) by the y/y change in inflation makes no sense. Empirically, the US economy has also done well despite a rising real rate.

We believe that productivity growth may be one of the most important factors in determining the neutral interest rate. Fiscal policy certainly matters as well. But the Fed commentators who oft-cite the neutral rate don’t seem to account for those two factors.

(7) Taylor Rule. The Taylor Rule is a mechanical formula for setting the FFR based on the unemployment rate (or economic growth) and inflation. As inflation has fallen, proponents of the rule suggest rates should, too. However, the rule depends on knowing how high the economy’s potential growth is, and what the neutral unemployment rate is (the rate that neither raises nor weighs on inflation). Of course, neither of these is measurable. If anything, we believe that higher productivity growth and immigration have raised the US economy’s potential, suggesting the model would advise a higher FFR.

Of course, anyone using the Taylor rule to set monetary policy would have ended easing and started raising rates much sooner than this Fed did (Fig. 26 below).

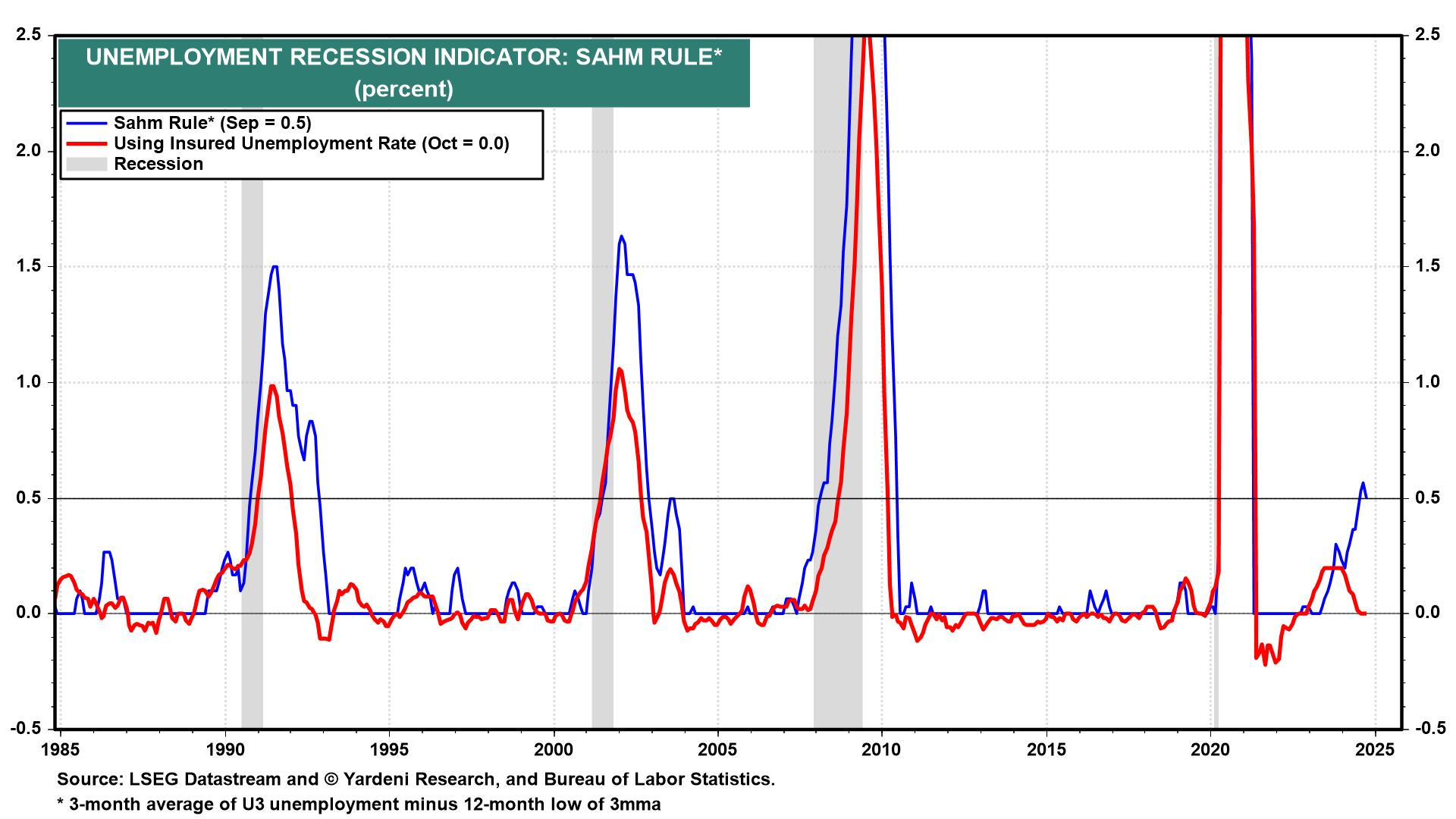

(8) Sahm Rule. The so-called Sahm Rule, a recession indicator based on the moving average of the headline unemployment rate, was triggered in July when the unemployment rate rose to 4.3% (Fig. 27 below). We dismissed this at the time as yet another false recession signal. That proved to be the right call, as the unemployment rate ticked down from 4.2% in August to 4.051% last month. Besides, soaring unemployment is associated with credit crunches and recessions, not with real GDP growing 3.0%!

(9) Excess saving. JP Morgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon warned in December 2022 that the exhaustion of excess savings and inflation would “derail the economy and cause a mild or hard recession.” We said that rising real wages, increased income from higher rates, and a very positive wealth effect would allow consumers to keep spending. Baby Boomers in particular would “dissave” as they retired during the pandemic, and soaring home and stock values would embolden them to spend.

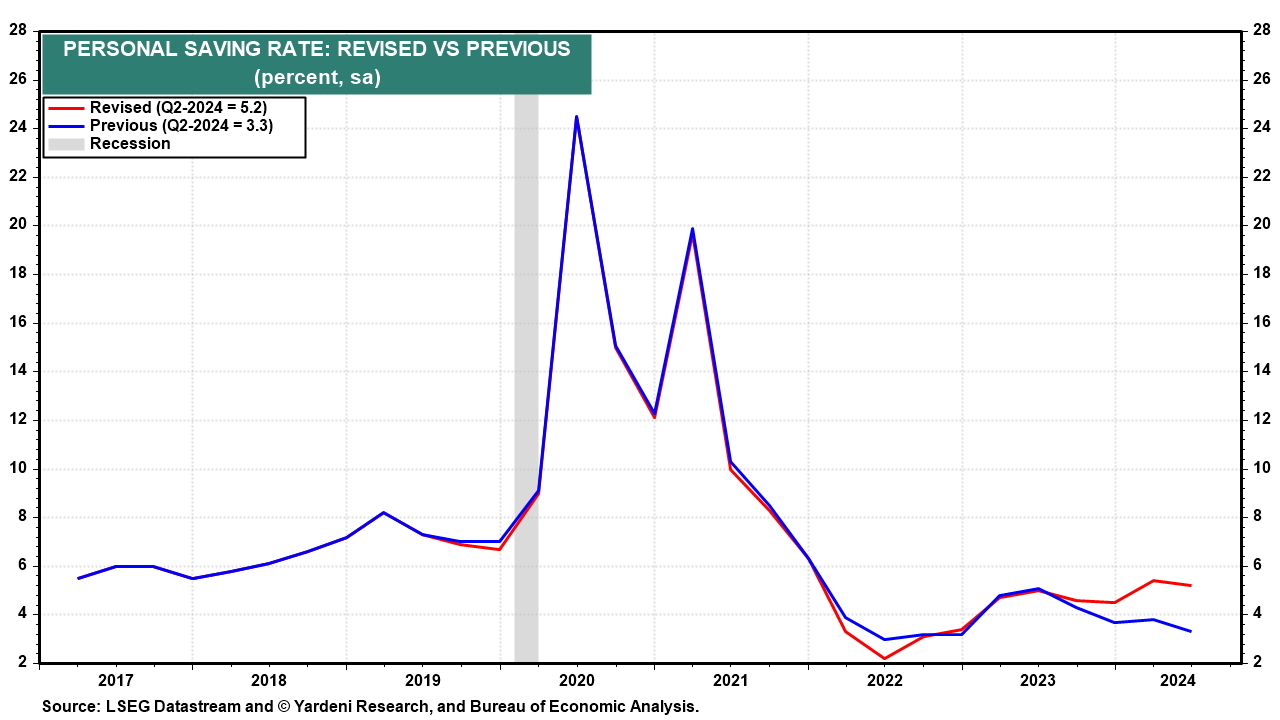

The latest revision from the Bureau of Economic Analysis found that nonlabor incomes were much higher in 2022 and 2023 than it had believed, which raised the personal saving rate from 3.3% to 5.2% as of Q2 (Fig. 28 below). It seems consumers haven’t exhausted their savings after all.

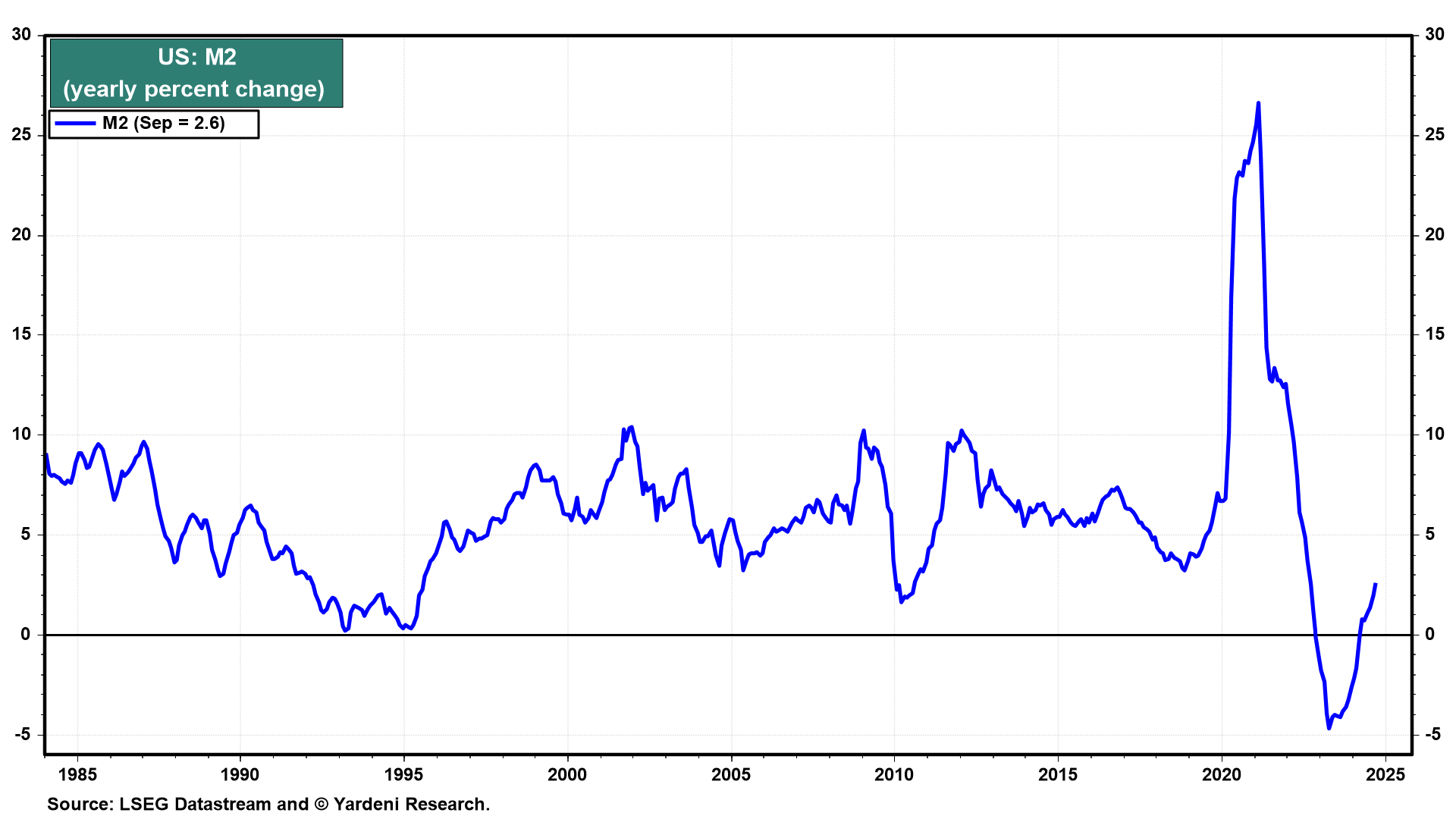

(10) Money matters. M2 money supply contracted from November 2022 through March 2024 (Fig. 29 below). Yet the stock market enjoyed a huge bull run and inflation moderated. That should have quieted the monetarist view that inflation is everywhere and always a monetary phenomenon.

Perhaps monetary policy is not the most important factor for economic growth. Productivity attributable to the efforts of the private sector may be more important, in our opinion. Furthermore, fiscal policy may quicken money velocity and encourage more consumer spending and business investment.