Inflation I: The Good

In our Roaring 2020s scenario, a productivity growth boom boosts real GDP growth, keeps a lid on inflation, drives up real labor compensation, and widens profit margins. Last week’s Productivity and Costs report compiled by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) mostly included revised data for Q3-2024, which mostly supported this upbeat outlook.

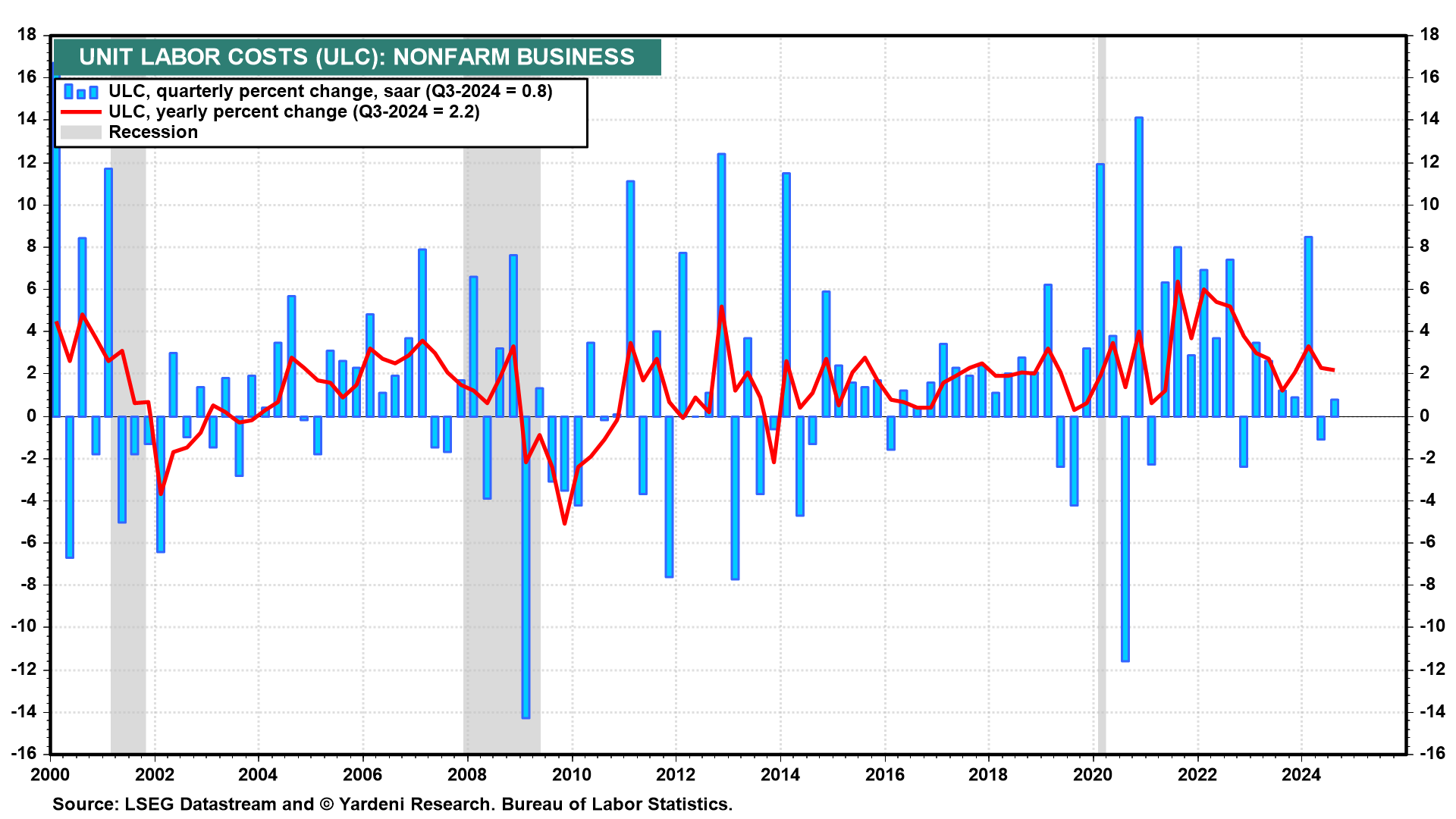

The most significant revision was in unit labor costs (ULC), which determines the underlying inflation rate in the labor market. It is calculated by BLS as hourly compensation divided by productivity. Q3’s ULC in the nonfarm business sector was revised down 1.1 percentage points to an increase of 0.8% (saar), reflecting an equivalent downward revision in hourly compensation to an increase of 3.1%. ULC increased 2.2% y/y, down from the 3.4% prior preliminary estimate (Fig. 1 below).

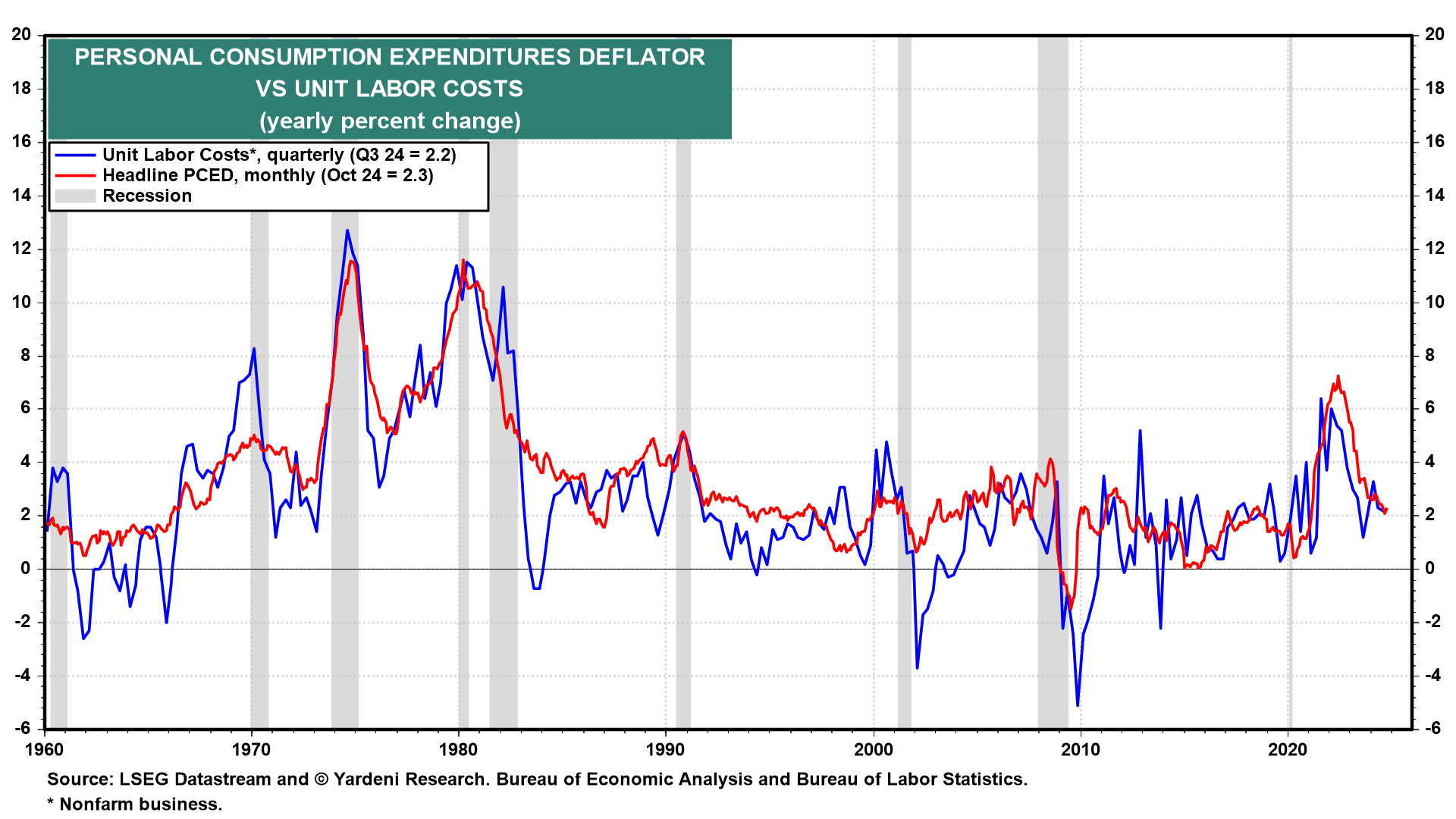

The y/y headline PCED inflation rate closely tracks the y/y ULC inflation rate (Fig. 2 below). The former was up just 2.3% through October, while the latter rose 2.2%. Both are down from over 6.0% in 2022. In other words, the decline in the ULC inflation rate was the major reason that consumer price inflation has moderated since its summer 2022 peak.

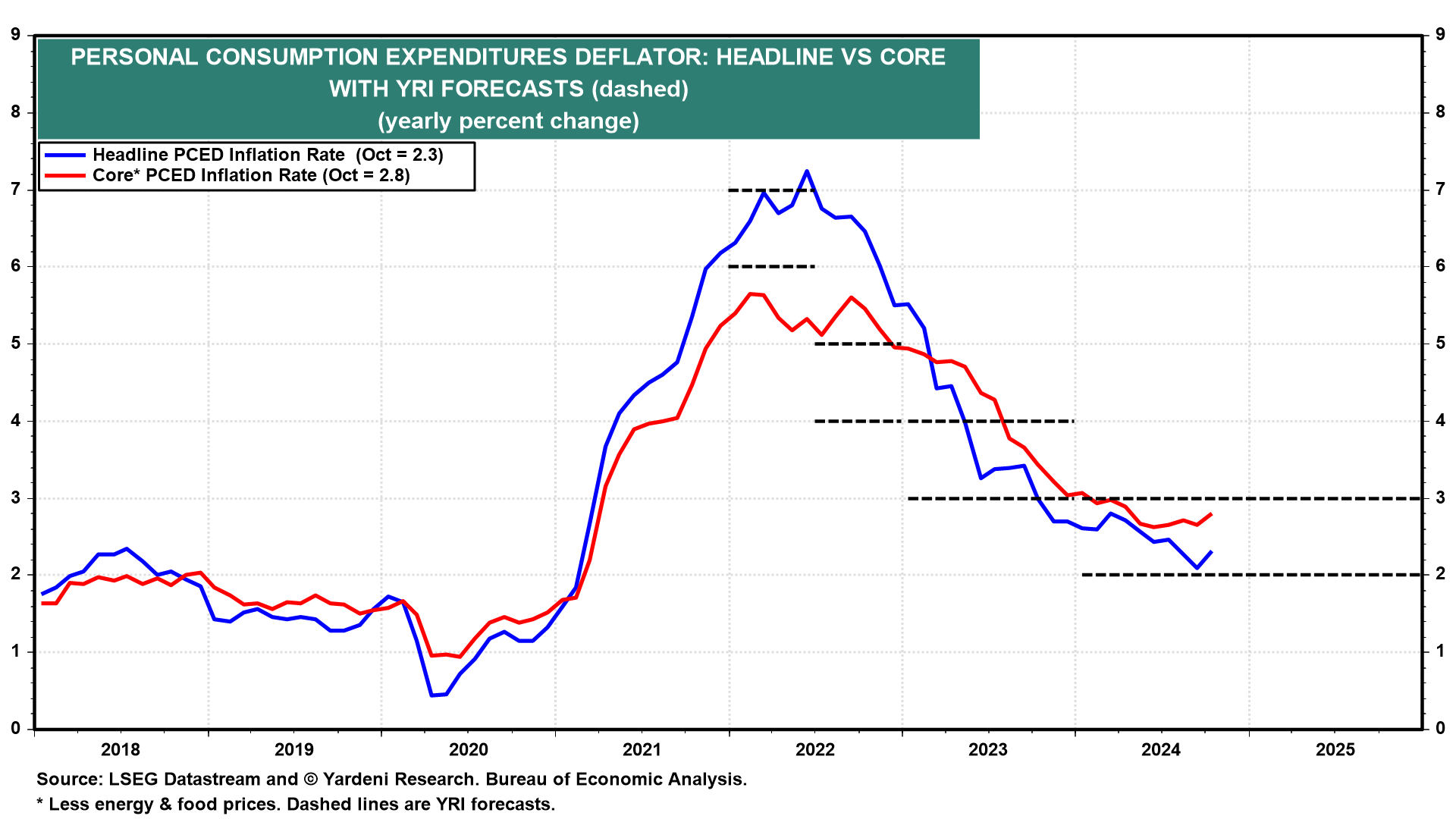

During the summer of 2022, Debbie and I predicted this moderation in the PCED inflation rate (Fig. 3 below). We expect it will remain in the current 2.0%-3.0% range through the end of 2025 and probably through the end of the decade. However, we have some concern that the Fed’s current monetary easing campaign might revive inflationary pressures in coming months by boosting demand for goods and services at the same time as fiscal policy remains very stimulative.

Regarding fiscal policy, Trump 2.0’s impact on inflation is a “known unknown.” Tax cuts would also boost demand for goods and services. Tariffs would likely cause a one-time increase in the inflation rate unless they are offset by a stronger dollar. Deregulation should be mostly disinflationary. Reductions in federal government spending would also be disinflationary, but they aren’t likely to be significant enough to affect inflation much either way. More energy production could help hold down not only energy prices but prices broadly.

All these crosscurrents could make for a confusing and volatile inflation story next year. However, we are betting that productivity gains will keep a lid on ULC inflation and therefore overall inflation in 2025, and through the end of the decade, and possibly through the 2030s. Now let’s focus on the latest productivity and ULC data in the context of our Roaring 2020s scenario: