On Tuesday, China announced a raft of policies aimed at boosting the economy and encouraging consumption. The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) cut its seven-day reverse repo rate from 1.7% to 1.5%. The central bank will also cut the amount of funds that lenders must hold in reserve by 0.5ppt, with more cuts expected later this year. And regulators will recapitalize China’s largest commercial banks; their margins and profits had been eroded by fee reductions and interest-rate concessions. On Wednesday, the central bank trimmed the cost of medium-term loans it provides to banks.

Regulators directly targeted the real estate market by lowering the down payment required on second homes from 25% to 15%. It will also offer better terms on loans to state-owned enterprises that are buying unsold apartment inventory from property developers. (The program launched in May has seen slow adoption, with local governments borrowing only Rmb24.7 billion out of the Rmb500 billion local banks made available, according to an August 20 FT article.)

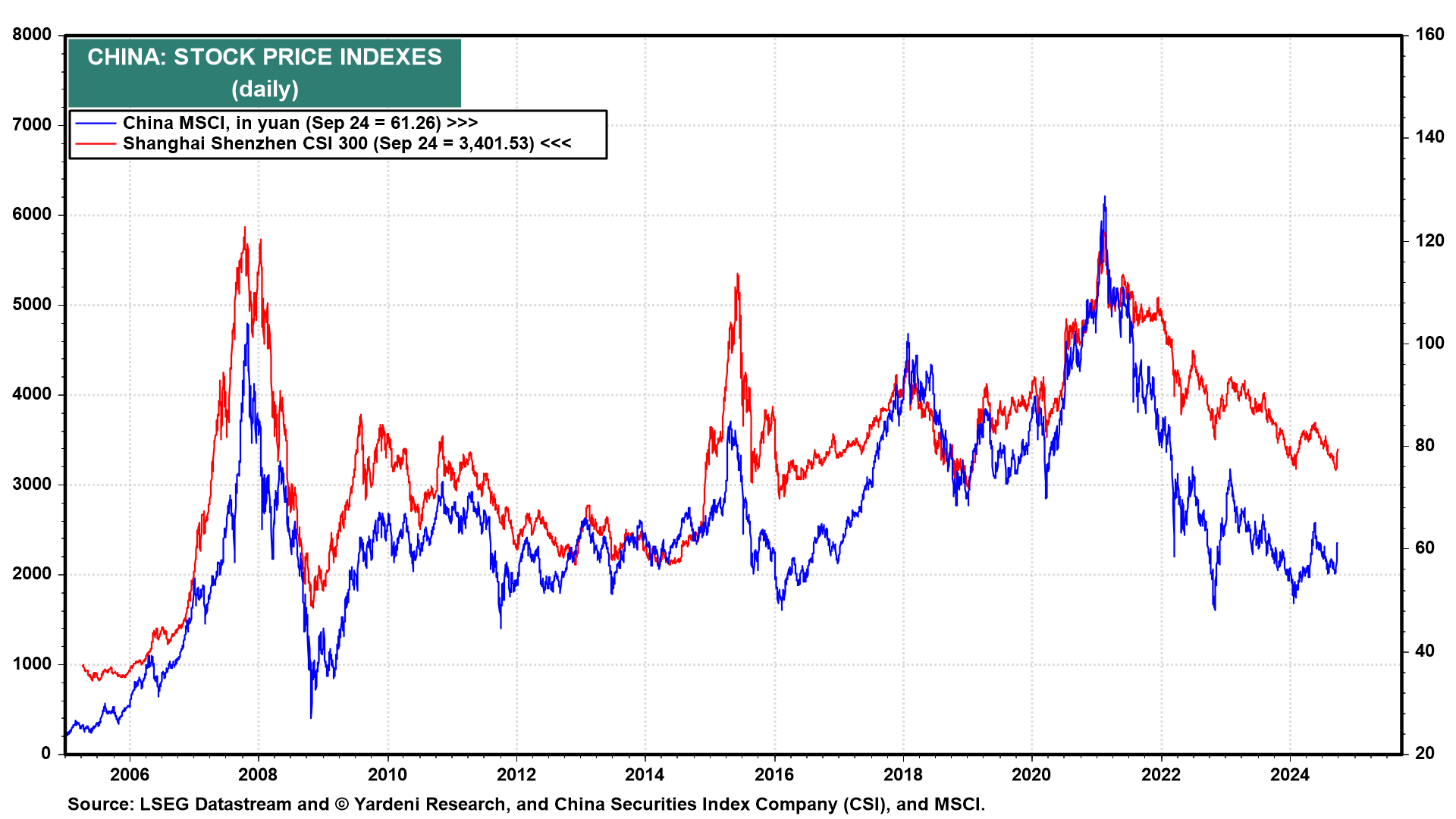

The Chinese stock market received some love as well. Regulators will provide the equivalent of $71 billion to help brokers, insurance companies, and funds buy stocks. The PBoC will also provide $114 billion to help companies buy back shares. Stock investors applauded, sending the CSI 300 5.9% higher on Tuesday and Wednesday (Fig. 9 below).

The good that these policies do may be offset by Chinese government actions that chill the willingness of consumers and companies to spend and invest in the country.

China’s recent threat to put Tommy Hilfiger’s parent on the national security blacklist doesn’t scream “come and invest in our country.” Neither does the detainment of an economist who criticized leaders in a private online chat. And China’s plan to increase its retirement age certainly won’t improve consumer confidence or encourage people to start spending. It’s almost as if China were writing a guidebook for economies on how to be one’s own worst enemy.

Here's a deeper look at government policies that may hurt future business investment and consumer spending in China more than the PBoC’s latest initiatives will help:

(1) How to scare corporations.

China’s commerce ministry has threatened to put PVH, the parent company of Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger, on its national security blacklist for not purchasing cotton from its western Xinjiang region. The company has 30 days to defend itself against the accusation that it has been discriminating against Xinjiang-related products over the past three years.

What was PVH thinking? Merely that it wants to sell its China-made goods in US markets: The US bans goods made in Xinjiang unless importers can prove that they were not made using the forced labor of the Muslim Uyghur population. So China’s blacklist threat places PVH between a rock and a hard place.

Five other companies are on China’s national security blacklist, including Lockheed Martin and Raytheon Technologies due to their sale of weapons to Taiwan. But they have no business in China at risk. PVH, on the other hand, has stores and warehouses in China. If placed on the list, the company could “face fines, have its activities in China restricted, or face other unspecified penalties,” a September 24 FT article reported.